Postnatal Depression Sent Me To The ER

I remember the night we ended up in hospital clearly.

Eleven weeks after giving birth and I was out of options. ‘Call an ambulance!’ I told my husband, Sam. It was past midnight and I hadn’t slept for 2 days. Not because I didn’t want to, but because I couldn’t. My mind was racing, my heart was pounding, I was spiralling.

The paramedic told Sam to take me to the closest emergency ward. In a frenzy, we packed some clothes, put our son in the capsule and headed for the hospital.

As we waited, tears streamed down my face. I pleaded with the nurse to give me something to make it all go away. I wasn’t suicidal but I felt like I was dying.

Looking back, I now know this is what they call ‘crisis point’. I needed help and I needed it quickly.

This piece is a submission by Kristy Tan.

Contents

What postnatal depression felt like

In the lead-up to that night, I already knew something wasn’t right.

I’d heard that motherhood was supposed to be tough, but this was impossible. My body had no strength, my heart had no hope. I was a shell of a person struggling to function.

I was also a new mum with a baby to love.

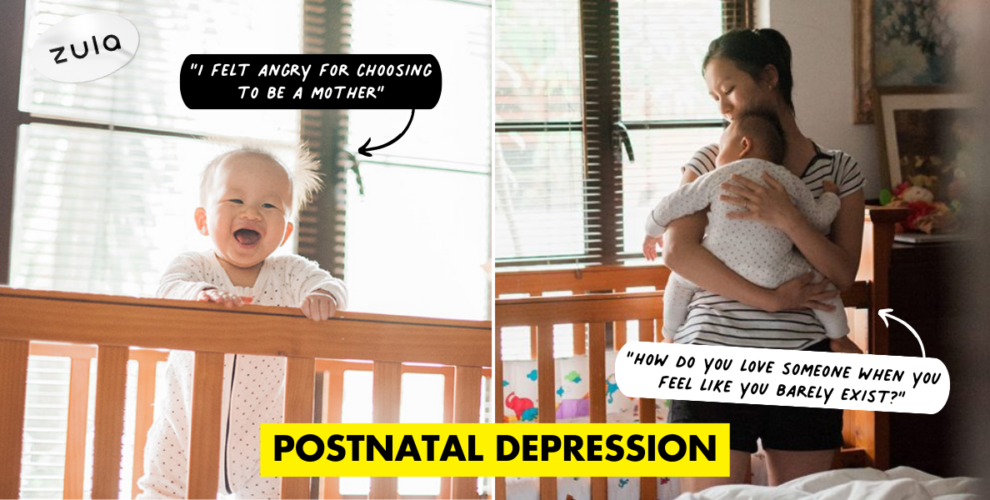

Joshua as a baby

Joshua as a baby

But how do you love someone when you feel like you barely exist? How do you give when you are empty?

That’s how postnatal depression (PND) and anxiety felt to me. I loved my son but was convinced that I couldn’t look after him. I was constantly tired, no matter how much I slept. Even though I had always been a passionate person, I had no interest in doing anything. Despite knowing there was nothing to be anxious about, I was nervous. I felt guilty, soulless, resentful and angry for choosing to be a mother and then feeling like a failure. I was constantly overwhelmed and depleted and consumed, all at the same time. Every day, I wished that I felt differently.

Also read:

I Have Depression But I Want You To Know Things Will Get Better

Why did it happen to me?

I remember going for a prenatal class and zoning out when they mentioned the risk of PND. I’m a capable, confident and contented woman. “This is not something I would struggle with,” I thought. I was arrogant or scared or maybe a bit of both, so I dismissed the idea. Thinking about it would only create a self-fulfilling prophecy, I convinced myself.

What’s more, PND had always seemed like a celebrity illness, one that only affected people with highly stressful lives. Perhaps I would have worried if I had a strained marriage or lots of financial issues, but I didn’t have any risk factors. I also hadn’t struggled with mental health disorders before, so I figured having a baby wasn’t going to affect that.

But it did.

Mental illness and stigma

And oh, how it did. It was only when I was going through it that I realised how mental illness doesn’t discriminate. Yes, there are risk factors that make it more probable. Things like relationship stress, financial burdens and past mental disorders, but it can affect anyone and it does. According to research, postpartum mental illness affects 1 out of 7 women (possibly more, as many go unreported). It also affects men.

I will also stress that mental illness affects Asians too. Unfortunately, in many Asian cultures like ours, mental illnesses are still highly stigmatised and very poorly understood. I had family members tell me that I just had to be more positive, as if it was all just in my head.

Then there’s the notion that people who struggle with mental illnesses are crazy and dangerous. I don’t deny that some mental illnesses do push a person to a point of insanity and danger, but often, most of us are just our usual selves needing some extra help or support for a certain period of time. We’re human and we’re struggling; and denying or minimising the illness doesn’t take it away. It makes it worse.

The recovery process

Giving Joshua a bath during my recovery at the mother and baby unit

Giving Joshua a bath during my recovery at the mother and baby unit

Fortunately, recovery, although extremely difficult, is very possible for most. Like anyone else struggling with a mental health issue such as anxiety and depression, one of the biggest challenges is feeling like you are your symptoms. It’s hard to separate the illness from your actual self. Part of the recovery process for me was learning to tell them apart and to believe that I was not my illness. I was a person who had depression. I wouldn’t let it have me.

Because my depression was severe enough, I was prescribed an antidepressant. I took one daily for the next 6 to 8 months. I was hesitant at first, but after trying natural ways such as exercise and socialising and finding no improvement, I knew this was something I had to do.

Over time, the fog lifted and I started to feel more confident as a mother

Over time, the fog lifted and I started to feel more confident as a mother

So I took the meds. I got lots of help from my parents and in-laws when it came to caring for my son, continued to journal as a means of therapy, and rested when I needed. I stopped pushing myself to be the mum I thought I should have been and accepted the mum that I was.

The guilt consumed me initially but I know now that there is no shame in getting the help you need. You do what’s best for yourself and for your family. Eventually, the fog lifted, and I started to feel more and more like myself. I couldn’t believe it but it did pass in the end. I weaned off my meds and am now the capable, competent and contented mother I hoped to be, somewhat.

How I Survived Postnatal Depression

Now, I look back and think about the suffering, and how postnatal depression stole so much from me in my first year as a mum. I could be bitter, but I hope to do better than that. So I choose to see what I have gained from the experience.

While the process of recovery was humbling, it was incredibly insightful. I developed empathy for other mental illness survivors and have such respect for anyone suffering from ailments both visible and invisible.

I learnt that even when it feels like the end, most times it isn’t; and grace carries us where striving can’t. Finally, I learnt that while we don’t get to choose what happens to us, we can do our best to use all of it for good. We can give purpose to our pain. We can make it part of our story. One someone else needs to hear.

This article was first published on 5 August 2019 and last updated on 4 April 2024.

Also read: