Life of a Singaporean Marine Biologist

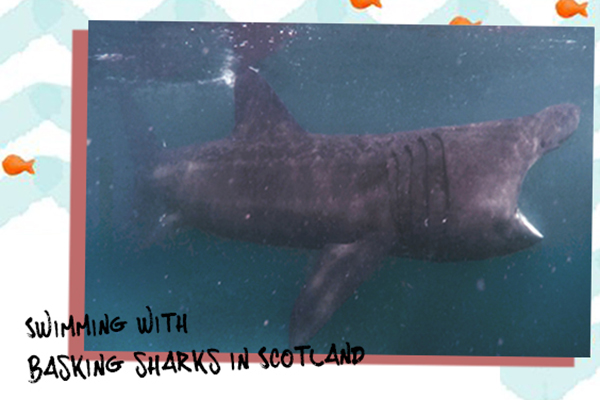

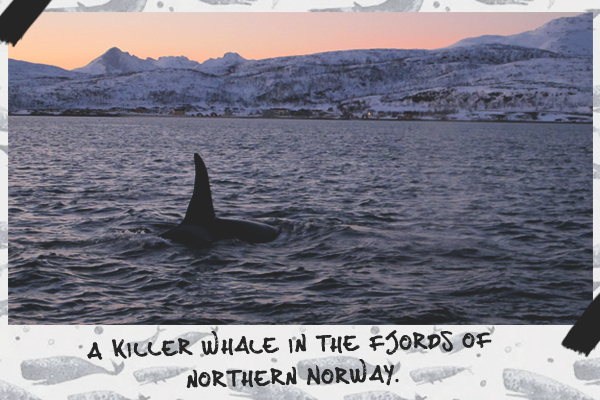

Continents apart, Tiffany earnestly fills me in about life abroad like a friend sending time capsules in postcards. While shuffling between Norway and Barcelona, she tells me of her fondest memories of freediving with sharks and watching killer whales feeding in the northern Norwegian fjords.

“I would love to tell you more about that!” she writes. “I love being out in the field, even if I have to wake up at 5.00am in the morning. The amazing sunrise always makes it better.”

“I am keen on the protection and conservation of marine life and the environment. Growing up in Singapore, I never knew the consequences of consuming shark’s fin soup, or how detrimental plastics are to marine life. And these are only two out of the many problems the oceans face.”

Ironically, the former Republic Polytechnic graduate was adamant she’d never do science again after earning a Diploma in Biotechnology.

She toyed with the idea of pursuing a “common and secure” business degree, and eventually worked as a business office administrator for Singapore General Hospital, and in the casino marketing team for Resorts World Sentosa (RWS).

“I wanted to be the best, but I didn’t know how to be the best at what exactly,” she recalls.

During her two-year stint at RWS, she chanced upon a laboratory technician role in the Department of Animal Health and Research at S.E.A Aquarium and took a significant pay cut to secure an internal transfer.

By working in the laboratory with aquarists and assisting vets, she discovered her interest in marine life. However, her university application was rejected.

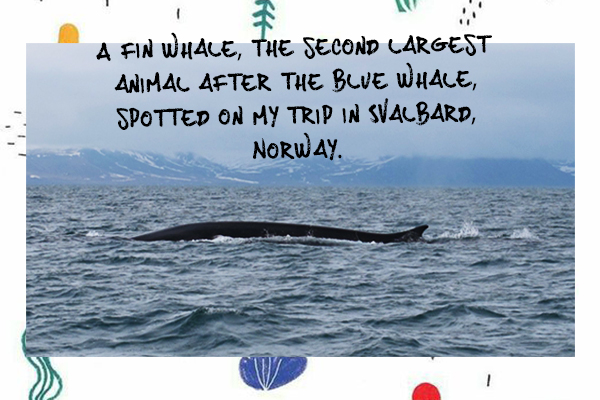

So, she left her job at RWS and dived straight into marine conservation through internships and long-term volunteer projects in the Philippines.

Here, she tells us about her first encounter with killer whales and the challenges of leaving the little red dot to venture into uncharted waters.

Contents

The first step into marine conservation (Philippines)

Tiffany:

Leaving my full-time job, relocating to a different country, and paying to volunteer were my hardest decisions to make.

I was afraid I was making a big mistake, but my family supported my decision. My boss/mentor also encouraged me to go all out and make the most of it because we grow through experience.

In the Philippines, I got accepted into the Zoox Experience Programme, an 8-week course which taught the fundamental knowledge on marine conservation. The practical and management skills I learnt were used to carry out assignments with the local government and communities.

My work supported Green Fins, a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) initiative which implements environmental-friendly guidelines within the diving industry to protect marine ecosystems.

I planned a seagrass monitoring programme with the local government and Fisheries Officer of Puerto Galera, Philippines. I collected data from the field, analysed it, and produced a report to the local authorities.

As a Green Fins Assessor, I also conducted environmental training sessions to dive staff and overcame language barriers to deliver scientific concepts to a non-specialist audience.

Zoox provided me with a reference letter, which I used to apply for the BSc (Hons) in Marine Biology at the University of Plymouth and got accepted.

A few months before my degree started, I went around the Philippines alone before deciding to volunteer as a researcher for a Non-Governmental Organisation, LAMAVE.

While collecting data on the whale shark population in Oslob, I picked up freediving to take photos of and identify sharks. I also learnt more about the ecology of the marine megafauna and how tourism impacts migratory species.

Studying whales in the Arctic

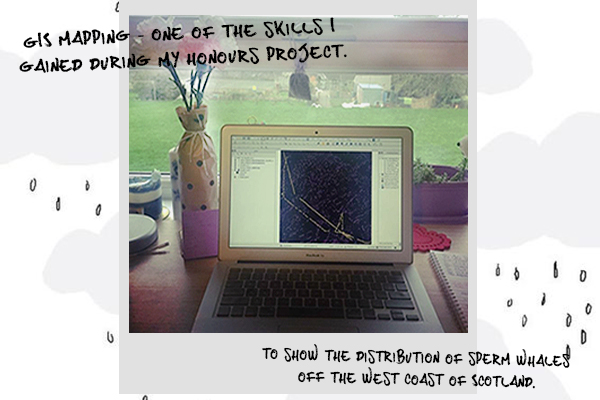

In 2014, I moved to England for my 3-year degree. In my final year, I did a module on the ecology and conservation of marine vertebrates and chose an Honours project on the habitat preference of sperm whales off the west coast of Scotland.

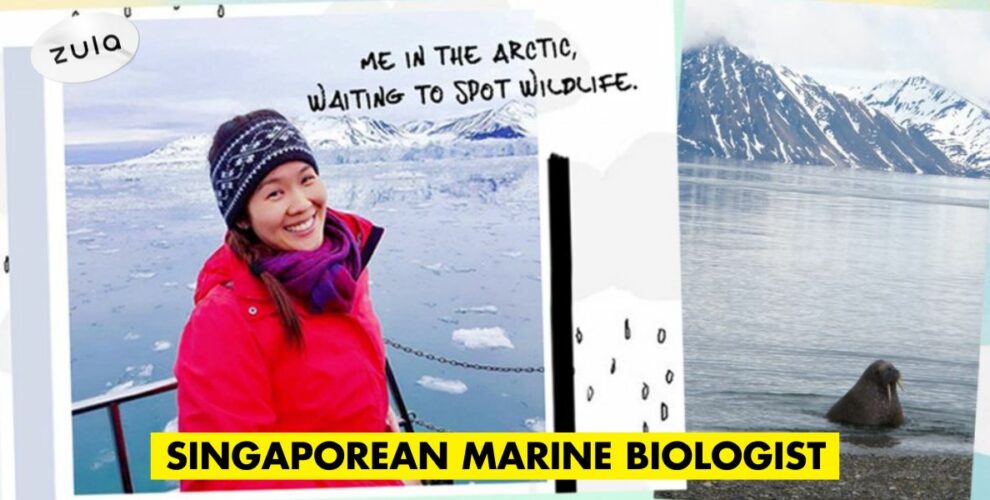

Whales and dolphins are highly intelligent. They have families (pods), their own calls, and ‘dialects’. Most species migrate large distances, such as humpback whales. They could spend winters in northern Norway and summers all the way down to the Caribbean.

To study cetaceans, we can attach satellite tags to track them, take pictures of their dorsal fin or tail flukes and also noticeable features to identify individuals. We can also detect them from the sounds they produce.

My unwavering desire to help conserve cetaceans (specifically whales) sparked when I first saw humpbacks and killer whales feeding in the northern Norwegian fjords, and the number of boats surrounding these whales.

With the increasing number of ships at sea, the boat engine sounds emitted can overpower whale communication in some species, affecting the mating process as whales have to ‘speak louder’.

Although the killer whales don’t seem to mind the noise just yet, environmental changes, potential oil exploration, and drilling in the Norwegian Arctic are some of the threats that may impact these whales.

Also read:

I Chose To Date A Guy Even Though I Was Moving Overseas In A Month & It Was An Amazing Decision

Struggles and prospects

After getting my degree, I was convinced that marine mammal research was my calling. However, I didn’t have the resources then; funding is important in this field and it doesn’t come easy due to the tough competition among researchers and the lack of belief in climate change.

I admit I lost myself many times in the past year. I sent out at least 50 job applications only to get rejected by all except one and had to overcome loneliness and anxiety.

But, I believe you can either follow a plan which restricts your life or take chances and learn from mistakes.

Ironically, the more I applied for jobs, the more I found myself wanting to pursue marine mammal research through academia. So I applied to the University of St Andrews—the only research-focused Master’s degree in Marine Mammal Science worldwide—and got accepted!

Protecting The Marine Environment

As Singaporeans, we like to complain and have things as convenient as possible. Back home, I always get shocked by the number of plastic bags my mum hoards in the cupboard. In Norway and England, they charge for bags. Even if they cost a few cents, a significant decrease in the demand of plastic bags has already been found.

But behind the complaints, I believe we are capable of being more environmentally-conscious, and it’s as easy as using a reusable water bottle and bag.

Aspiring scientists like myself persevere because we desire to find answers to our many questions and to protect marine animals through our research.

I hope by sharing my story, other girls will not only be inspired to go off the beaten track but also realise everyone can do their part in protecting the marine environment.

This article was first published on 10 July 2018 and last updated on 23 May 2024.

Also read:

Singapore Zoo’s First Female Elephant Keeper Shares Why Not All Zoos Are Prisons